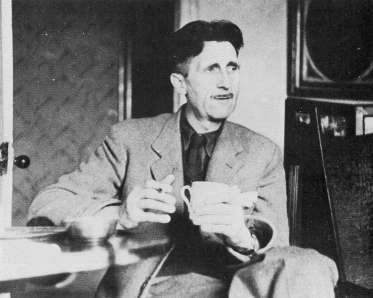

Back in the 1920s, George Orwell (alias of Brit Eric Arthur Blair), lived and worked in Burma (what is now an area of India) as an Imperial officer and agent of the British police. A few years after his return, he wrote several essays on his experience as a white man in Burma, which are an insightful read into the times and experience of the British empire in India - if you are ever able to get your hands on a collection of them, please do. The particular collection I own is a British edition containing essays from across Orwell's career - from his early writing career to Burma to his return and purposeful life as a homeless man in Europe.

Back in the 1920s, George Orwell (alias of Brit Eric Arthur Blair), lived and worked in Burma (what is now an area of India) as an Imperial officer and agent of the British police. A few years after his return, he wrote several essays on his experience as a white man in Burma, which are an insightful read into the times and experience of the British empire in India - if you are ever able to get your hands on a collection of them, please do. The particular collection I own is a British edition containing essays from across Orwell's career - from his early writing career to Burma to his return and purposeful life as a homeless man in Europe.While in India, Orwell's essys kept coming to mind. During my hospital stay, flashes from Orwell's experience in a French hospital (captured in the essay "How the Poor Die") came to the forefront. While driving past slums and ramshackle houses in Kolkata, "The Spike" surfaced.

Most poignantly, however, was the morning we met an Elephant.

In the collection of Orwell essays that I own, the title essay - "Shooting an Elephant" - is the reason I bought the book. It is probably the most anthologized Orwell essay that exists as it is accessible, tells an interesting story, and has implications that reach far beyond itself. In this essay, Orwell tells about one incident that happened to him while in Burma, one that he says was "a tiny incident in itself, but it gave [him] a better glimpse ... of the real nature of imperialism - the real motives for which despotic governments act." What is that motive? We see the answer in the story: An elephant breaks free from his trainer and goes rampaging through the village. It destroys a truck, some fruit stalls, and, in an act of uncontrolled "must" (we would say that the elephant was in heat), kills a man by grinding him into the ground.

Upon realizing the elephant may be dangerous, Orwell exchanges his small Winchester rifle for one specifically designed for killing elephants. This alerts the villagers to the idea that something exciting might happen, and eventually a crowd begins following Orwell as he goes to the paddies where the elephant has settled. Orwell compares this to the way an English crowd might follow if something exciting was happening in their town. Orwell, however, knows that what he plans to do and what the crowd expects him to do are two distinct actions - and mutually exclusive ones at that. He merely has the rifle to defend himself should the elephant prove dangerous; the crowd expects that he will shoot the elephant. At this crucial moment of decision, Orwell writes, he realized that he "was only an absurd puppet pushed to and fro by the will of those yellow faces behind." He has no option but to shoot the elephant, if only to hold on to his own authority in the village. "To come all that way, rifle in hand, with two thousand people marching at my heels, and then to trail feebly away, having done nothing - no, that was impossible. The crowd would laugh at me. And my whole life, every white man's life in the East, was one long struggle not to be laughed at."

Why in the world would this pop into my head during the trip?

At one point, one of the girls mentioned off hand to our Indian guide that seeing an elephant would be cool. Ever eager to please, he took us one morning to a circus in Vizag, to show us an elephant. We were all shocked and surprised, and happy...at first. By the end of the day, most of us cited meeting the elephant as the low point of our day, and I will do my best to clarify why, though it may tangent into several different ideas.

Walking into the circus, we wondered if we were supposed to be there. There were large crowds of Indian men - the largest amount of people composed of solely males I had seen since we'd landed. The gateway to the circus was decorated with advertisements for the circus, featuring pictures of only women, none of them smiling, which I noticed was a little odd. We ducked under a chain through a gate, and walked through the dust and sand to where two elephants were chained up. Our group greeted them with excitement and the girls started taking their turns getting pictures touching an elephant, in India! How often do you get to do that?

I stood at the edge of the group, taking pictures and talking to my friends Chase, Althea and Will, who were all rather quiet and clearly not okay with what was happening. A little dense at first, I soon realized that their annoyance at the whole thing was not the distraction from getting to breakfast, but the condition of the elephant itself and the circumstances surrounding it.

I took another look, this time actually seeing the elephant. I was shocked to discover the heavy and short chains on its feet, not allowing it to walk in a circle much larger than five feet. The elephant itself was covered in dust and looked slightly skinnier than the elephants I'd seen previously in zoos. It was then that the trainers started making the elephant do tricks and I noticed the pokers in their hands. This weren't the somewhat humanitarian cattle prods that I've seen used in the States - these were little pokers, as in fireplace pokers that you might use for stoking a fire on a cold winter night: little metal sticks with a sharp pointy end. At that point, I walked away, out of sight of the elephant, though it was a few minutes longer before we could actually leave to go back to the bus.

We were hampered on our way, however. Our group was stopped on our walk back to the bus so that the crowd of men - by now having tripled in size - could take pictures of us in front of the circus' signs. I commented to my friend that I felt like I was in a zoo as the men whipped out cell phones and small digital cameras and snapped pictures of the white people visiting.

This is the second time on the trip I remember feeling weird about being white. The first was during my hospital stay, when I realized that I was the only white person in the room and that was why every Indian who passed by the foot of my bed did a double take. These incidences were not isolated, and I soon became used to the stares that said, "Hey look, white people!" At this point, however, the cameras and zoo-like atmosphere only inspired discomfort and lack of enthusiasm to be white anymore.

It was in these few moments standing as a group being posed for pictures that Orwell's words returned to mind: the white man's whole struggle in the East is the effort not to be laughed at. This idea was hard to shake over the next few days as I felt as though we were being paraded through comunities and towns as though we were some freakishly absurd animals on display, instead of symbols, actors and reasons for both their oppression and hoping for their liberation. Many times, if we were not hailed as celebrities, we were a curiosity, something to be stared at and studied as though behind glass, and, occasionally, laughed at.

While Orwell writes from an openly imperialistic age, one that allowed him to see quite easily how the white man oppresses those in Burma/India, we live in a world where drawing the lines of oppression requires a study of the global economy, and much research. It is hard to see how what I purchase on Saturday affects the life of my Indian friend on Monday, but globalization dictates that this principle is true. The lines of production, while hidden, are there, and often include hands smaller than my own, holding no hope beyond the shoe factory where they eke out a living.

It was not until nearly our last day that things really began to click for me. In visiting Mypadu, I felt for once that I was not on display, and the reason was that I actually had time and chance to know some of the villagers. Orwell's problem was that the massive crowds behind him, urging him to shoot the elephant or be laughed at, were not people to him. They were merely, as he calls them, "two thousands wills." Because he remained separate - and, indeed, his role as a tool of the British government demanded it - he could not move beyond this idea that there was any role between white and, to use his word, "yellow" beyond tyrant and tyrannized.

When we spend time getting to know people, we cannot maintain our old roles of oppressed and oppressed. We can no longer be slave driver and slave, warden and prisoner, client and prostitute.

To risk making this shallow by making a Harry Potter reference, Voldemort's major failure as a wizard, and the thing that kept his evil so powerful, was that he separated himself from community - he never got to know even those who were his servants, and that allowed him to convince himself that he was in the right. Those most powerfully against Muggle rights and Muggle-born wizards in the books are those who do not know any Muggles or Muggle-borns themselves.

It is through intense, powerful, dynamic relationships that lives change.

It is when we become friends with one poorer than us that we understand what truly creates poverty.

It is when we befriend a child at risk for becoming a slave that we realize the true evil of slavery.

It is when we know a handicapped person that suddenly "retarded" is no longer okay.

It is when we get to know a gay person that fighting against homosexual marriage becomes pointless.

It is when we become friends with the Chinese family next door that racism loses its sting.

It is this that Orwell both realized and failed to realize. If he allowed the crowd to crystallize into being actual people rather than merely faceless wills, he might not think that he was there to be laughed at.

But then again, he might have lost his power as a tyrant, and thus, his job.

No comments:

Post a Comment

The owner of this blog tolerates no form of hate speech, including racial slurs, citing stereotypes as fact, or anything else deemed intolerant or hateful by the blog author. While you may have a right to say it, it does nothing to advance productive discussion, and therefore any comment containing such speech will be deleted accordingly.